The ecstasy of Saint Theresa

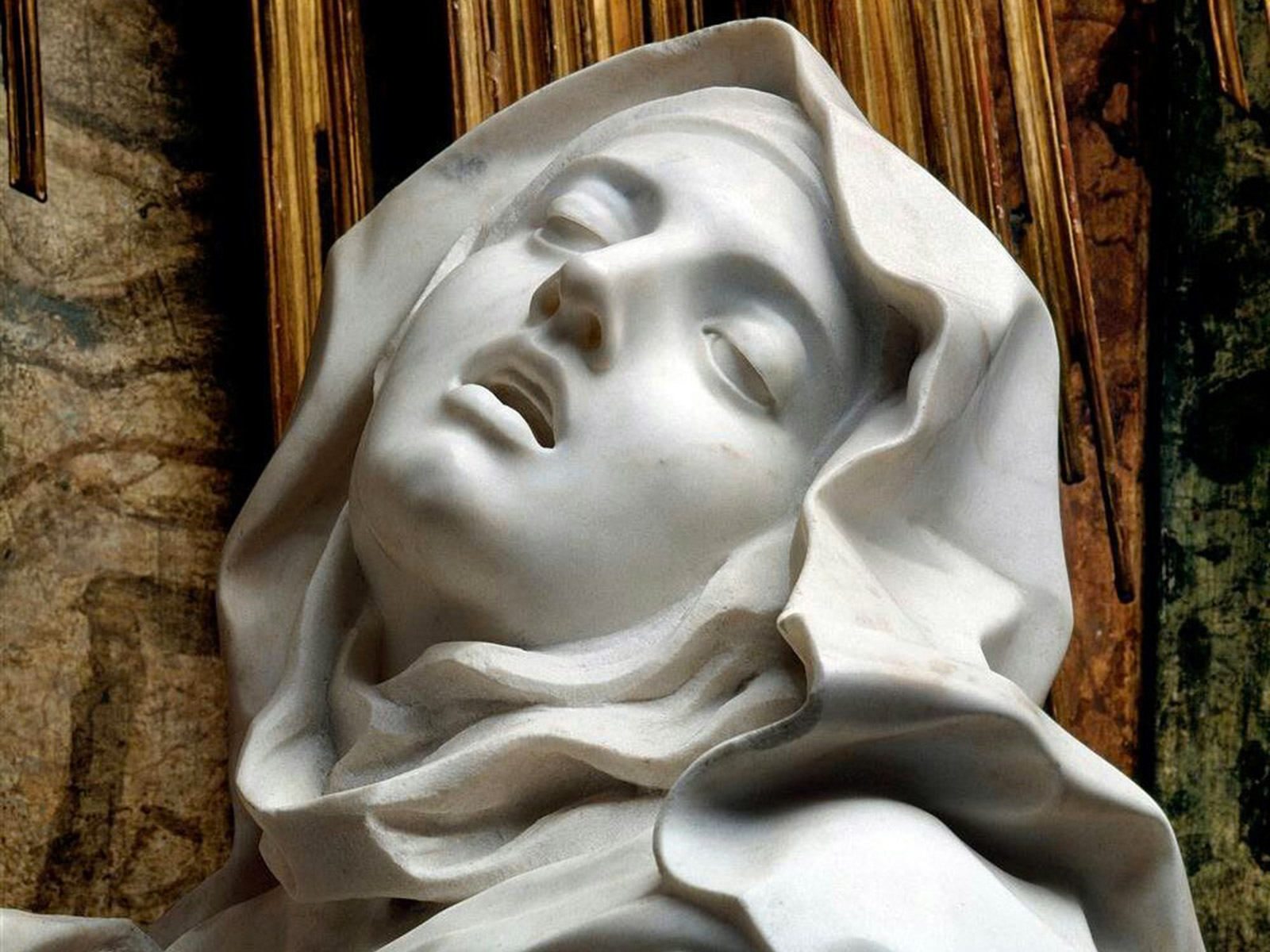

A balustrade separates the viewer from Bernini's Saint Theresa, created by the artist between 1647 and 1652 for the Cornaro family chapel in the church of Santa Maria della Vittoria in Rome. The effect Bernini seeks is a measured distance between the viewer and the sumptuous marble epiphany: the correct position for the faithful before the mystical experience, which can be approached, but not conveyed through words. And yet the number of interpreters who have attempted to penetrate the mystery of Teresa of Avila (1515-1582) is endless: a saint by chance, and ironically the greatest icon of the Counter-Reformation. The biography, tastefully reconstructed with acumen by Vita Sackville-West, cannot be ignored: her birth in Castile ‘of stones and saints’, the fourth of twelve siblings, her flight from her father's house to enter the monastery of the Incarnation, a second ‘conversion’ at the age of forty, and the publication of The Book of Life at fifty, a maze of memories of family and love, and at the same time the complete laying bare of a soul: almost a form of therapy through writing that allowed the woman to build herself. And then again, at an age that would have made the silence of the cloister advisable, a whirlwind of travel, politics, reform: mistrusting the papacy, Teresa ‘the wanderer’ founds eighteen monasteries in twenty years; with a serious whiff of heresy, Teresa ‘the possessed’ triumphs over the Inquisition, which tries but does not condemn her; from the alumbrados to St John of the Cross, a whole heterodox world, obviously male, is at the crossroads of this ironic, strong-willed, witty rebel: ‘O Lord, deliver me from the holy snouts,’ she appears to have asked God.

This restless spirit could not help but question psychology: and so, Saint Teresa imposes herself on the conscience of psychoanalyst Silvia Lequerc, the protagonist of Julia Kristeva's fluvial novel dedicated to the Spanish saint. As a roommate of her ‘underwater nights’, Teresa invades Silvia's life, but also becomes an opportunity for her to understand herself and the women she meets in therapy. A dreamy and majestic serenade, Teresa, My Love, which is difficult to summarise: but we can share some key concepts here.

First of all, mysticism as a revolution: our era relegates mysticism to contemplation, yet the very minds (and often bodies) of mystics have always been, Kristeva suggests, a secret laboratory of visions and conceptions capable of imagining other worlds, of renewing thought and institutions. Second, and here the definition is Teresa's own, the idea of the personality as an ‘inner castle’: an apparatus with many rooms, multiple transitions and facets. Therefore, it is not a castle in which identity is entrenched, but rather a kaleidoscope in which it unfolds, loses itself, and frees itself. Our identity is one, three, perhaps elusive: it took the Baroque to represent this turbulence.

Third, ecstasy and its meaning: what does Teresa enjoy? No, sex has nothing to do with it: for Freud, Teresa was the patroness of hysteria, but Lacan had already ruled out any libidinal motive. ‘Ce n'est pas ça du tout.’

Instead, ecstasy must be traced back to the literal meaning of ex-stare and its meaning is all in that prefix: ‘to be outside of’, outside oneself. That means to immerse oneself in the infinite desire of the other, of the absolute Other, of the divine that penetrates as if it were a spouse. The ek-static Ego is the Ego dragged out of itself: a contagious pleasure that involves and upsets all the senses.

‘Bùscate en mì’, seek yourself in me, is the title of a speech that Teresa delivered to general bewilderment in 1577: formulated, it seems, by repeating the words that God had dictated to her. And this ‘Seek yourself in me’, Kristeva tells us, is not the ‘Know thyself’ engraved on the pediment of the temple at Delphi: which in the end was only an invitation to be wise, from Apollo to his worshippers. Nor is it the ‘What do I know?’ of Montaigne, in which the Christian faith, though not repudiated, was clouded with doubts. Nor the Cartesian ‘I think, therefore I am’, which reduced all certainty to the thinking subject.

Teresa's Ego is born instead ‘outside of herself’ because it is born together with the love of the Other and for the Other. Teresa comes to us to tell us that self-knowledge takes place only in the splitting, in the transference of our deepest bonds. ‘The souls who love see down to the atoms,’ Silvia says in a Molly Bloom monologue, and in this exploration, we finally become intelligible to ourselves. Such fullness – intimate, very personal – cannot be preached. And it is perhaps for this reason that while a dart pierces the heart of the saint, Bernini's angel laughs ‘stupidly’.