Happy are those who are different - Poetry and the prose of love, between Sandro Penna and André Aciman

Nicole Riva

“Happy are those who are different / being different. / But woe to those who are different / being common.”

These lines, a true manifesto of diversity in all its facets, opens Sandro Penna’s second collection of poetry, Appunti, published in 1950 by La Meridiana. With the calm and tranquillity that distinguish his verses, the poet rejoices in the discrepancies that exist between him and the literary and social environment of the time. Born in Perugia in 1906, he moved to the capital at the end of the 1920s and began writing his first poems, which would be appreciated by many great poets of his time, including Saba, and in 1939 he published his first collection, although many friends and colleagues expressed hesitation. From this brief biographical description, which is not intended to be exhaustive, Sandro Penna appears to be just one of the many authors who dot the Italian literary collections of the twentieth century, but this is not the case. He was an isolated man, "very jealous of his wild solitude": he rarely went out, did not attend worldly events and lived in seclusion and surrounded by his papers. Even at the stylistic level, the poet deviated from the norm; in the decades dominated by Montale's hermetic poetry, he stands as an anti-modernist, with revivals ranging from classicism to twilight poetry. Penna's writing is clear and limpid, spontaneous and natural, linked to a single major theme that led him to be on the fringes of the literature of his time: homosexuality. Openly homosexual, he had two great love affairs, a youthful one with Ernesto and a later one with Raffaele, who was much younger than him. Love for young men is the cornerstone of his poetic works and some of his deliberately provocative statements; he writes in Poems: “Always children in my poems! But I don't know how to talk about other things.”

Having homoeroticism as a fundamental theme during Fascism and in the post-war years could have seriously compromised Sandro Penna as a poet, yet that diversity and marginality that we have talked about so far was not only the result of the non-acceptance of poetry by society, but above all a personal choice. Penna had complex creative phases, made up of poems hidden in drawers with false bottoms or in upside down fruit boxes under his bed. In any case, Sandro Penna's “different” poetry has never really been censored and has been positively criticised by many Italian literary greats, first by Pasolini, but also Saba, Montale, Gatto, Gadda and Ginzburg. In 1957, his collection titled Poesie won the Viareggio Prize in its second edition, despite half of the jury judging his verses to be too rough. I believe that the success of Penna's poetry, which is certainly elitist and unfortunately still studied too little, is due to the candid and sublime style with which he describes love, from the passions without guilt to the irresponsible happiness of those moments that then hide the bitterness of the end. The verses of Sandro Penna and the innocence of his words have the scent of the last days of summer, after spending the whole season on vacation among the shores of Porto San Giorgio to discover first loves and one's own sexuality, a bit like the summer described by André Aciman in his novel Call Me by Your Name.

The story takes place in a small Ligurian village during the 1980s; the family of Elio, a cultured and inexperienced young teenager, hosts an American university student, Oliver, for the summer. A timid attraction arises between the two, resulting in a love never hindered by their difference in age or the discovery of homoeroticism. The novel is characterised by a very poetic style, there is no perversion between the lines, only sweet naivety. The story is completely narrated by the young Elio and contains all his thoughts: fears, feelings and disappointments. On the contrary, Penna's poems are written by the adult who falls in love with the young man, as if this time it was Oliver who was telling the story. I can imagine Oliver, after being kissed by Elio among the blades of grass yellowed by the summer heat, returning to the house, closing the door behind him and leaning against the wood, thinking: "Maybe youth is just this / perennial loving the senses and not repenting.” However, it is not only these verses that provide a parallel between the two works: in the last chapters of the novel, the summer is about to end, Elio and Oliver take a trip to Rome and, intoxicated, run through the streets of the Eternal City, full of happiness that will shortly be exhausted with the end of the season and Oliver's return to the United States. I can hear them singing in the streets: "Let's go, let's go desperately / still together in the late night / and light and velvety summer." In the same way, I wouldn't be surprised if, in a bizarre fictional game, it turned out that the phrase "Call me by your name and I'll call you by mine" had been written by Penna and then hidden behind the frame of a painting.

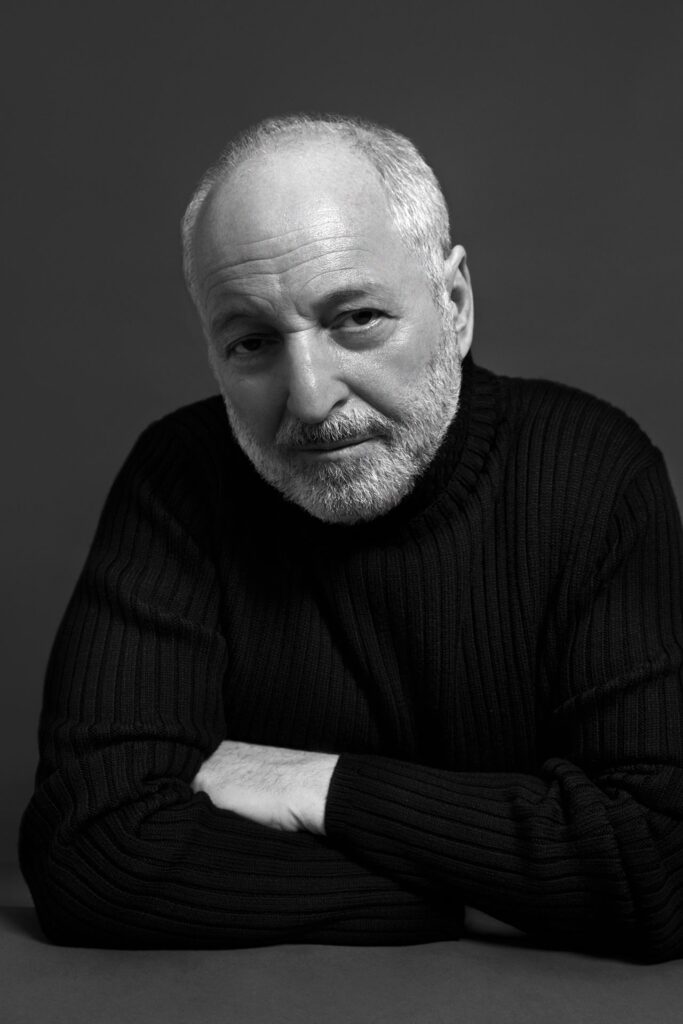

We have said that Penna writes about a "different" love and if we want to keep this line of thought, Aciman also describes a "non-traditional" love; yet the latter, during the presentation of his latest novel, Cercami, expressed feeling close to the character of Elio. At that moment, in the audience, I thought that all those who are capable of loving, regardless of the object of their love, are Elio. On the other hand, it remains a bit more difficult to identify with the totality of Penna's poems, which can sometimes convey a bitter aftertaste, due to the poet's provocative streak, but which certainly does not prevent us from considering him one of the greats of the last century.